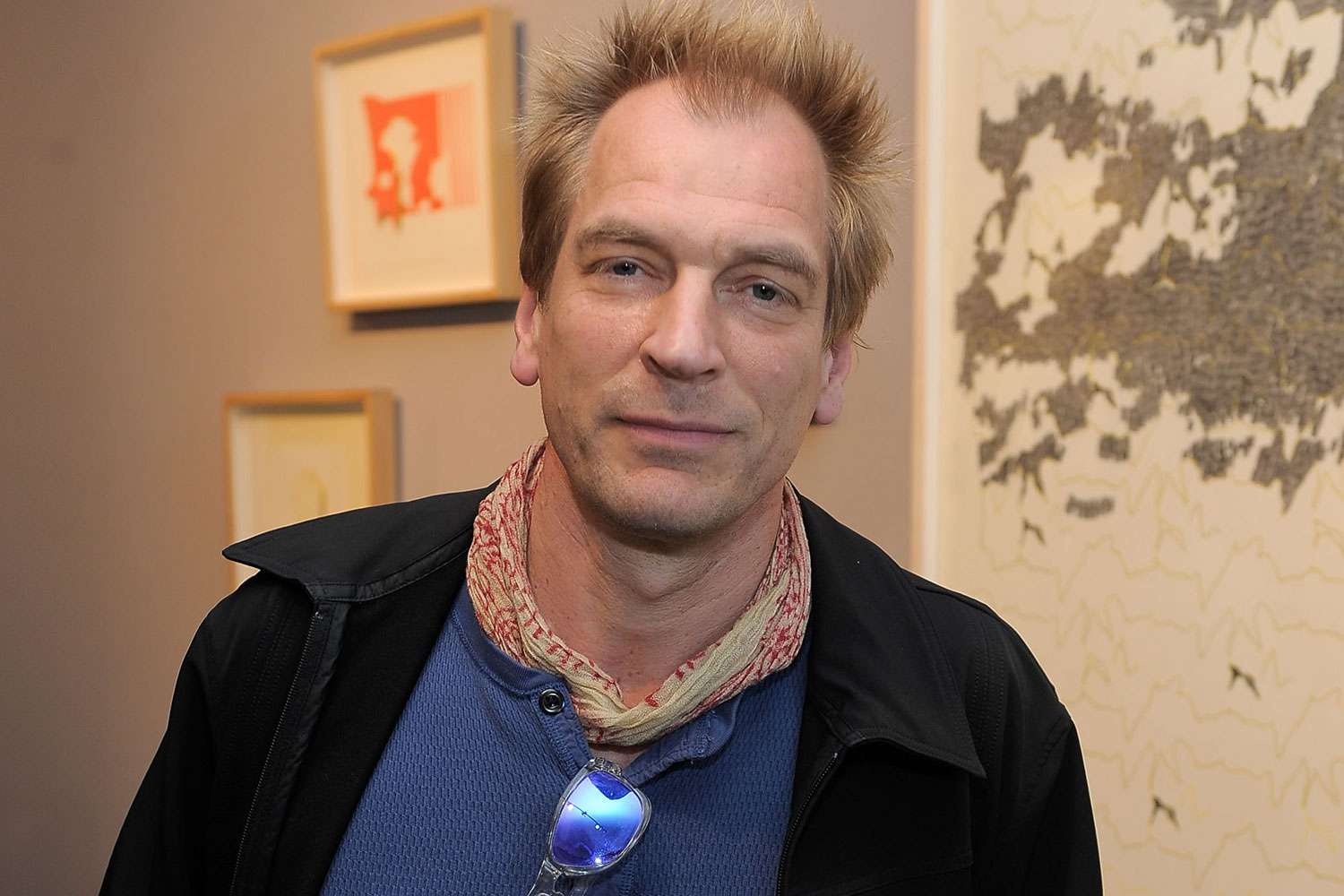

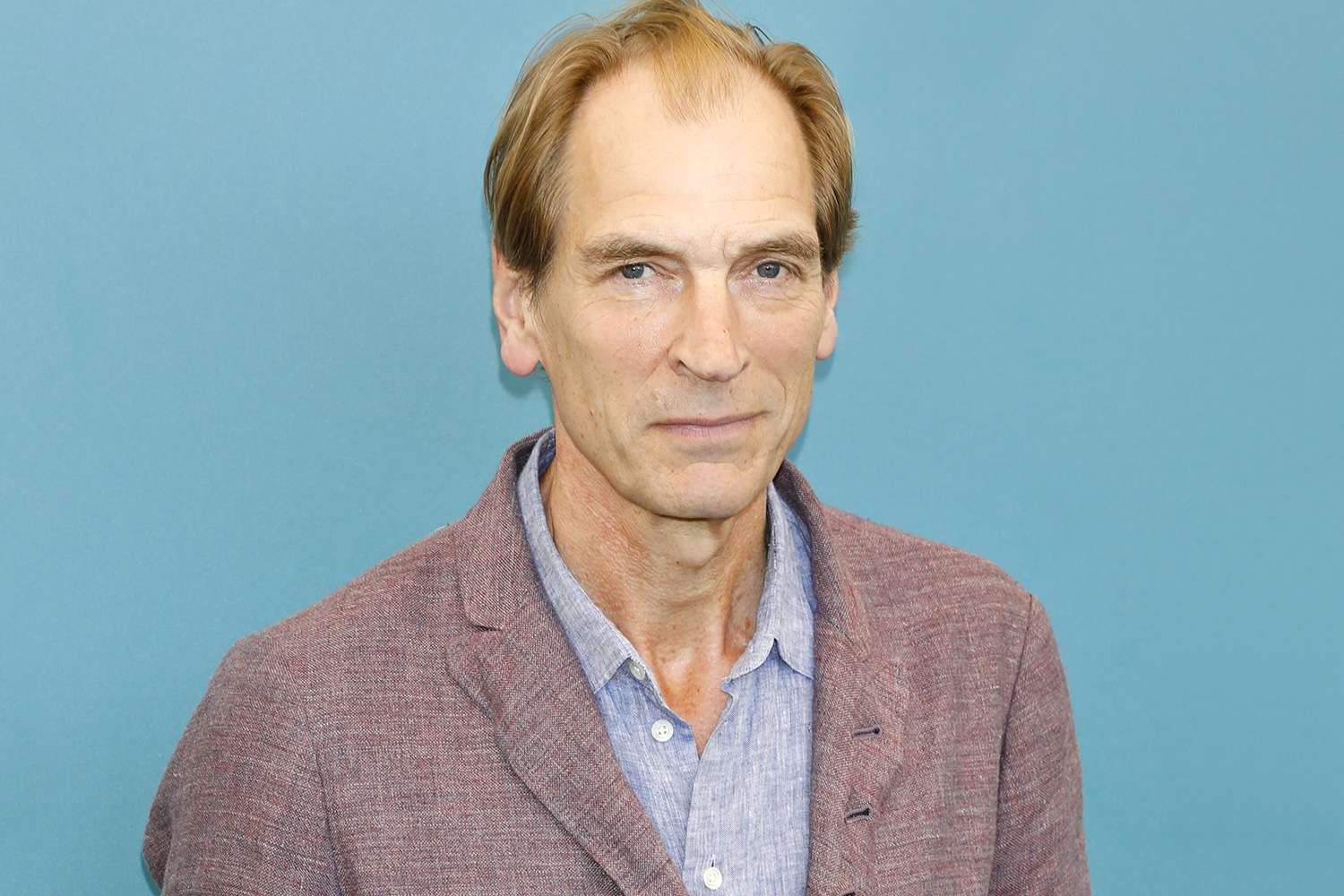

On Friday, Jan. 13, the actor Julian Sands set off for a hike up Mount Baldy in California’s San Gabriel Mountains. He had done this kind of thing before: Mountain hiking was his passion. The 10,000-foot Mount Baldy is a difficult climb, but he had seen worse. In the Andes, he and three friends had reportedly been caught at 20,000 feet in a storm so violent, nearby climbers died. “We were lucky,” he later said.

Mr. Sands didn’t make it down from Mount Baldy that day. The San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department began a ground search, but it has so far come up empty. Looking for missing hikers and climbers is very difficult under the best of conditions, and especially so in winter. Ferocious storms across the western United States have since made the prospects even bleaker.

A friend of Mr. Sands’s recently described him as “an extremely advanced hiker” as well as “very, very fit.” Regardless, plenty of people will think this kind of expedition reckless. They will criticize those who set off in poor weather, in winter, knowing they could come to harm, for underestimating the risk. For going alone. For going anyway.

I am used to people telling me my chosen hobby is risky, even “insane.” I’m not a mountain hiker, like Mr. Sands, but I, too, have devoted myself to a sport I enjoy despite — and to some degree because of — the danger.

My love is fell running. “Fell” is an English term, from the Old Norse “fjall,” a mountain. In the north of England, and especially in Lakeland, the high, sometimes featureless hills are called fells, and the runners who like to run up and down and along them — and the hills of the Peak District and Yorkshire and elsewhere — are fell runners.

www.nytimes.com

www.nytimes.com